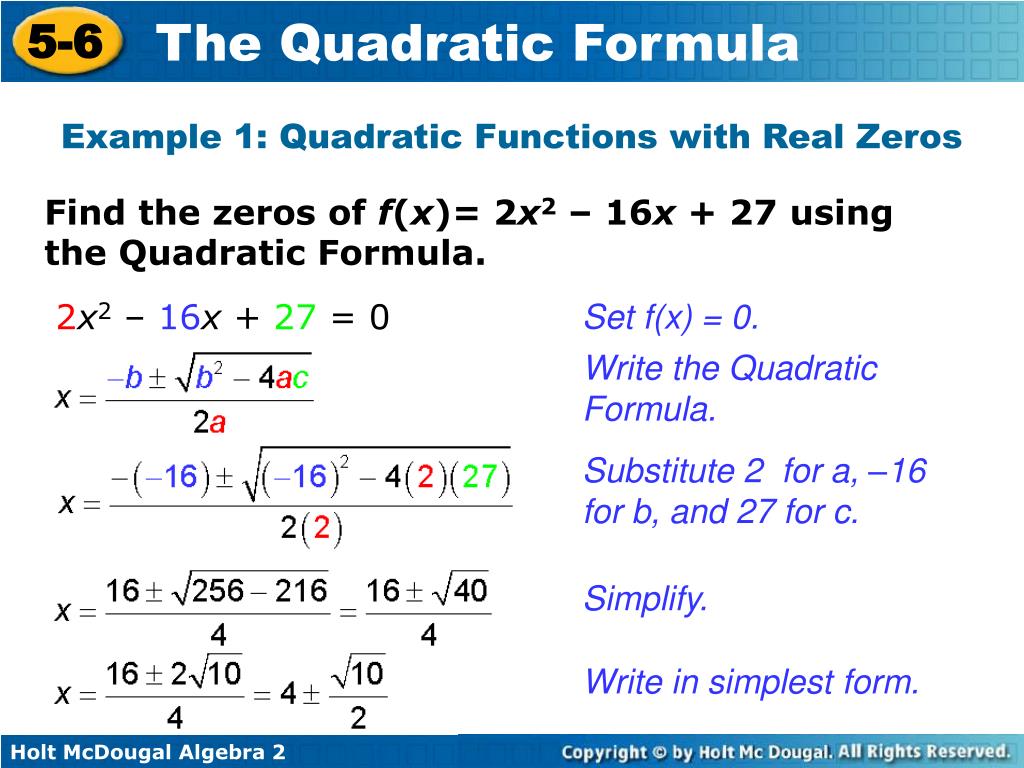

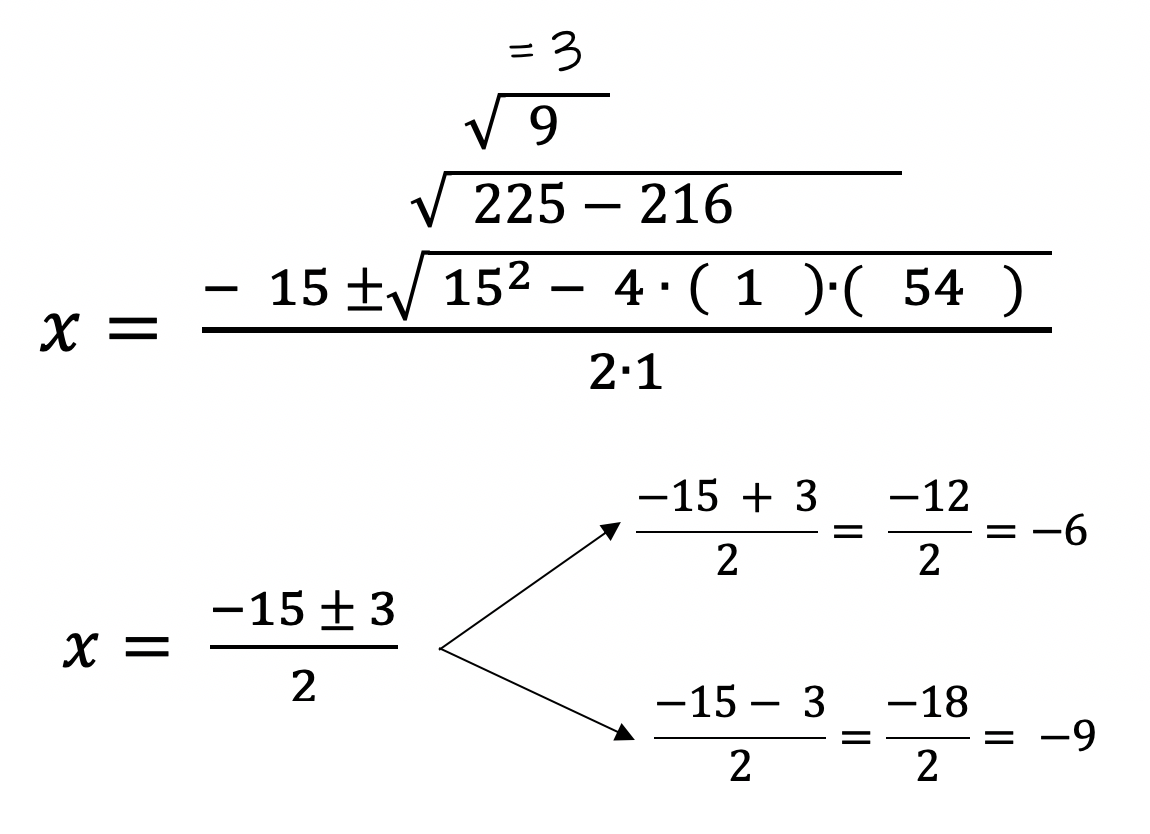

To find the roots, set y = 0 and solve the quadratic equation 3x 2 - 12x + 9.5 = 0. For example, enter the value 0 into cell A2 and repeat steps 5 to 9. Excel finds the other solution if you start with an x-value closer to x = -1. Click in the 'By changing cell' box and select cell A2. Click in the 'To value' box and type 24.5Ĩ. On the Data tab, in the Forecast group, click What-If Analysis.ħ. You can use Excel's Goal Seek feature to obtain the exact same result. The roots of a quadratic function are the x-coordinates of the x-intercepts of the function. i.e., they are the values of the variable (x) which satisfies the equation. High School Math Solutions Quadratic Equations Calculator, Part 1. For a given quadratic equation ax 2 + bx + c 0, the values of x that satisfy the equation are known as its roots. We need to solve 3x 2 - 12x + 9.5 = 24.5. quadratic-equation-solve-using-quadratic-formula-calculator.

But what if we want to know x for any given y? For example, y = 24.5. The process is known as ‘completing the square’.3.

#Quadratic formula equation series#

The Babylonians would solve this via a series of steps that illustrate the close connection between algebra and geometry. The parentheses here tell you to multiply each of the things inside the parentheses by the thing immediately outside it, which leads to: The area of a rectangle is simply the breadth multiplied by the length, so the area A is given by this equation: If the breadth is x, the length is x + 7. The area of a rectangle is 60 and its length exceeds its breadth by 7.

#Quadratic formula equation how to#

To see how, let’s return - as ever, it seems - to the ancient practices of taxation.Īs we saw in our look at geometry, taxes were often based on field areas - the Babylonian word for area, eqlum, originally meant ‘field’. It’s no wonder that Babylonian administrators had to learn how to solve puzzles like this one offered up on the ancient Babylonian tablet YBC 6967, which sits in the Yale collection: Although we typically learn them as distinct topics - mostly because it makes it easier to design school curricula - algebra flows seamlessly from geometry it is geometry done without pictures, a move that liberates it and allows the mathematics to flourish. In structuring this book, I have drawn an artificial distinction between algebra and geometry. If you are intimidated by the idea of algebra, with all its enigmatic notation, you might benefit from thinking of it as just a way of translating geometric shapes into written form. He generalized the known parameters to a, b, and c the unknowns were designated x, y, and z. But other sources say that it is down to René Descartes, who simply put the two extremes of the alphabet to work in his 1637 book La Géométrie. And so we ended up with the letter that makes the Spanish ‘ch’ sound: x. When medieval Spanish translators were looking for a Latin equivalent, they used the closest thing they have to ‘sh’, which doesn’t actually exist in Spanish. According to cultural historian Terry Moore, it’s because al-Khwārizmī’s original algebra used al-shay-un to mean ‘the undetermined thing’. Two men were leading oxen along a road, and one said to the other: “Give me two oxen, and I’ll have as many as you have.” Then the other said: “Now you give me two oxen, and I’ll have double the number you have.” How many oxen were there, and how many did each have?Īnd while we’re on the subject of notation, it’s worth noting that the reason that the letter ‘x’ became associated with the unknown thing is still hotly disputed. An early student of the Cossick Art might find themselves face to face with something like this: The sought-after hidden factor was usually referred to as the cossa, or ‘thing’, and so algebra was often known as the ‘Cossick Art’: the Art of the Thing. Algebra was originally ‘rhetorical’, using a convoluted tangle of words to lay out a problem, and to explain the solution. Al-Khwārizmī gives us prescriptions - formulas we call algorithms - for solving the basic algebraic equations such as ax 2 + bx = c, and geometrical methods for solving 14 different types of ‘cubic’ equations (where x is raised to the power of 3).Īt this point in history, by the way, there was no x, nor anything actually raised to any power, nor indeed any equations in what al Khwārizmī wrote. This pulls together Egyptian, Babylonian, Greek, Chinese, and Indian ideas about finding unknown numbers, given certain others. Algebra’s name comes from the word al-jabr in the title of Muhammad al-Khwārizmī’s 9th-century book (we met it in Chapter 1 as The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)